Steve Jobs did not invent the personal computer, the smartphone, or the digital music player. What he did was more profound: he understood what these technologies could mean to human beings before anyone else could articulate it. The man who built the most valuable company in history was neither the best engineer nor the most accomplished businessman of his generation—he was something rarer: a person who could see the invisible connections between technology and humanity, and who possessed the will to make others see them too.

Jobs died on October 5, 2011, at age fifty-six, leaving behind a company worth more than $350 billion and products used by hundreds of millions of people. But the true measure of his influence lies not in market capitalization but in the way he fundamentally altered our relationship with machines. He made technology personal, intimate, beautiful—and in doing so, changed what we expect from the tools we use. His life arc, from hippie dropout to visionary billionaire, from public humiliation to triumphant return, offers a case study in how a particular kind of mind—intuitive, obsessive, often cruel, deeply feeling—can reshape the world.

A seeker’s education in the infinite

Before Steve Jobs was Steve Jobs, he was a barefoot college dropout searching for enlightenment on a mountainside in India. At nineteen, with a shaved head and dysentery, he traveled with his Reed College friend Daniel Kottke through the Kumaon Hills seeking Neem Karoli Baba, a guru who had inspired the countercultural movement back home. The guru had died seven months earlier. Jobs spent seven months wandering anyway.

He returned to California with a profound realization that would shape everything that followed. “We weren’t going to find a place where we could go for a month to be enlightened,” he later reflected. “It was one of the first times that I started to realize that maybe Thomas Edison did a lot more to improve the world than Karl Marx and Neem Karoli Baba put together.” The sentence captures something essential about Jobs: the synthesis of spiritual seeking and material creation, the belief that building things could itself be a form of enlightenment.

What India gave Jobs was permission to blend ambition with transcendence. Buddhism, he discovered, “allows for more engagement with the world than is permitted ascetic Hindus.” He could pursue personal enlightenment and world-changing products simultaneously. This wasn’t compromise—it was integration.

Back in California, Jobs began studying with Kobun Chino Otogawa, a Japanese Zen priest who would remain his spiritual advisor for nearly thirty years. They met almost daily in Jobs’ early career, and later weekly at his office “to counsel him on how to balance his spiritual sense with his business goals.” When Jobs wanted to become a monk, Kobun refused to ordain him. “He had some big things to do,” the priest reportedly said. The more practical reason: Jobs couldn’t sit still for more than an hour.

The Zen influence permeated everything Jobs created. “If you just sit and observe, you will see how restless your mind is,” he explained. “If you try to calm it, it only makes it worse, but over time it does calm, and when it does, there’s room to hear more subtle things—that’s when your intuition starts to blossom and you start to see things more clearly.” His trademark uniform—blue jeans and black Issey Miyake turtleneck—was essentially a Westernized version of the samue, a monk’s plain working outfit. His products embodied the Zen aesthetic: nothing extraneous, every element purposeful, complexity hidden beneath serene surfaces.

The LSD experiences of his youth reinforced this vision. Jobs was remarkably candid about psychedelics throughout his life, calling them “one of the two or three most important things I have done in my life.” The drug, he said, “shows you that there’s another side to the coin, and you can’t remember it when it wears off, but you know it.” What he took from those experiences was a profound sense that consensus reality was negotiable—that what most people accepted as fixed limitations were often just failures of imagination.

The calligraphy that launched a thousand fonts

After dropping out of Reed College, Jobs continued auditing classes that interested him—including a calligraphy course taught by Robert Palladino, a former Trappist monk. The choice seemed purely aesthetic; Jobs had noticed that every poster on campus was “beautifully hand calligraphed” and wanted to understand how it was done.

“I learned about serif and sans serif typefaces, about varying the amount of space between different letter combinations, about what makes great typography great,” he recalled at Stanford in 2005. “It was beautiful, historical, artistically subtle in a way that science can’t capture.” Ten years later, when designing the Macintosh, “it all came back to me. And we designed it all into the Mac. It was the first computer with beautiful typography.”

The calligraphy story has become Jobs mythology, but its deeper significance lies in what it reveals about how he thought. The class had no practical application when he took it. Only in retrospect did its value become clear. This was Jobs’ theory of creativity: “You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backward. So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future.”

This trust in seemingly useless experiences distinguished Jobs from conventional business leaders. “A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences,” he observed. “So they don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective on the problem.” The broader one’s understanding of human experience, he believed, the better the design.

Where technology marries the humanities

Jobs repeatedly positioned Apple at what he called “the intersection of technology and liberal arts.” At the iPad 2 launch in 2010, he stood before a slide showing two street signs—”Liberal Arts” and “Technology”—meeting at a crossroads. “It’s in Apple’s DNA that technology alone is not enough,” he declared. “It’s technology married with liberal arts, married with the humanities, that yields us the results that make our hearts sing.”

This wasn’t marketing language. It reflected a genuine conviction about how great products emerge. “Part of what made the Macintosh great was that the people working on it were musicians, poets and artists and zoologists and historians who also happened to be the best computer scientists in the world.”

His design partner Jony Ive articulated the practical implications: “Simplicity isn’t just a visual style. It’s not just minimalism or the absence of clutter. It involves digging through the depth of the complexity. To be truly simple, you have to go really deep.” Achieving elegant simplicity required understanding not just the technology but the humans who would use it—their desires, frustrations, and unarticulated needs.

Jobs learned to appreciate simple interfaces at Atari, where video games “had to be made simple enough that a stoned freshman could figure them out.” The Star Trek game’s instructions were legendary: “1. Insert quarter. 2. Avoid Klingons.” This lesson—that complexity is the enemy of adoption—informed every product he later created.

How his mind actually worked

Jobs famously took long walks to think, particularly for important conversations. Biographer Walter Isaacson noted that “taking a long walk was his preferred way to have a serious conversation.” He and Jony Ive were constantly seen strolling the Apple campus, working through design problems in motion. If Jobs couldn’t solve a problem in ten minutes, he believed the solution required stepping away and walking—letting his mind make unexpected connections.

Stanford research later validated what Jobs intuitively knew: walking boosts creative thinking by an average of 60%. The effect persists even after sitting back down. Jobs wasn’t scrolling or distracted during these walks; he let his wandering mind do its wandering.

His meditation practice, rooted in Zen, served a similar function. Apple began offering meditation classes to engineers in 1999, years before such programs became corporate fashion. Jobs believed that quieting the mind created space for subtler insights to emerge.

But focus, for Jobs, meant something specific—and counterintuitive. “People think focus means saying yes to the thing you’ve got to focus on,” he explained at the 1997 WWDC. “But that’s not what it means at all. It means saying no to the hundred other good ideas that there are. You have to pick carefully. I’m actually as proud of the things we haven’t done as the things I have done. Innovation is saying ‘no’ to 1,000 things.“

When Nike CEO Mark Parker asked Jobs for advice, the response was characteristically blunt: “Nike makes some of the best products in the world. Products that you lust after. But you also make a lot of crap. Just get rid of the crappy stuff and focus on the good stuff.”

The reality distortion field and how it worked

In February 1981, software developer Bud Tribble coined a term that would define Jobs’ management style. When new employee Andy Hertzfeld questioned the impossible ten-month deadline for shipping Macintosh software, Tribble explained: “The best way to describe the situation is a term from Star Trek. Steve has a reality distortion field. In his presence, reality is malleable. He can convince anyone of practically anything. It wears off when he’s not around, but it makes it hard to have realistic schedules.”

The reference was to “The Menagerie,” where aliens create virtual realities through sheer mental force. Jobs possessed something analogous—a “confounding mélange of a charismatic rhetorical style, an indomitable will, and an eagerness to bend any fact to fit the purpose at hand.”

What made the reality distortion field genuinely strange was that it worked even when you knew it was happening. “Amazingly, the reality distortion field seemed to be effective even if you were acutely aware of it,” Hertzfeld observed, “although the effects would fade after Steve departed.”

Bill Gates, one of the few people largely immune, described it as “casting spells”: “I was like a minor wizard because he would be casting spells, and I would see people mesmerized, but because I’m a minor wizard, the spells don’t work on me.”

The field’s power lay in making people believe they could achieve what seemed impossible—and then actually achieving it. When Corning CEO Wendell Weeks told Jobs they couldn’t produce enough glass for the iPhone launch, Jobs responded: “Do you know what your problem is? You’re afraid.” Corning delivered. When engineer Larry Kenyon explained why reducing Mac boot time was technically impossible, Jobs cut him off with a calculation: five million users, ten seconds saved per boot, equals 300 million seconds per year—approximately 100 human lifetimes saved annually. A few weeks later, Kenyon had the machine booting twenty-eight seconds faster.

Reframing problems rather than solving them

Jobs didn’t solve problems the way other technologists did. He reframed them entirely, questioning whether the problem as stated was even the right problem to solve.

When Apple decided to make a phone, the conventional question would have been: “How do we improve existing smartphones?” Jobs asked something different: “What should a phone be?” The distinction mattered enormously. The former question leads to incremental improvements—better keyboards, faster processors. The latter leads to questioning whether phones need physical keyboards at all.

The iPod emerged from a similar reframing. Existing MP3 players were, in Jobs’ assessment, “all crap.” The industry framed the problem as: “How do we fit more songs on a small device?” Jobs reframed it as: “1,000 songs in your pocket.” This wasn’t a technical specification—it was a human experience definition. The technology had to serve that vision.

When Jon Rubinstein visited Toshiba in early 2001 and saw a tiny 1.8-inch, 5GB hard drive they didn’t know what to do with, he immediately grasped its potential. That night, he told Jobs: “I know how to do it now. All I need is a $10 million check.” Jobs wrote it immediately. Apple secured exclusive rights to every disk Toshiba could produce.

The Apple Store concept came from asking: “What should buying a computer feel like?” Jobs observed that “buying a car is no longer the worst purchasing experience. Buying a computer is now No. 1.” He and retail chief Ron Johnson asked who offered the best customer service in the world. The answer wasn’t another retailer—it was The Four Seasons hotel. The Genius Bar concept emerged directly from the hotel bar, dispensing advice rather than alcohol.

Simplicity as the ultimate sophistication

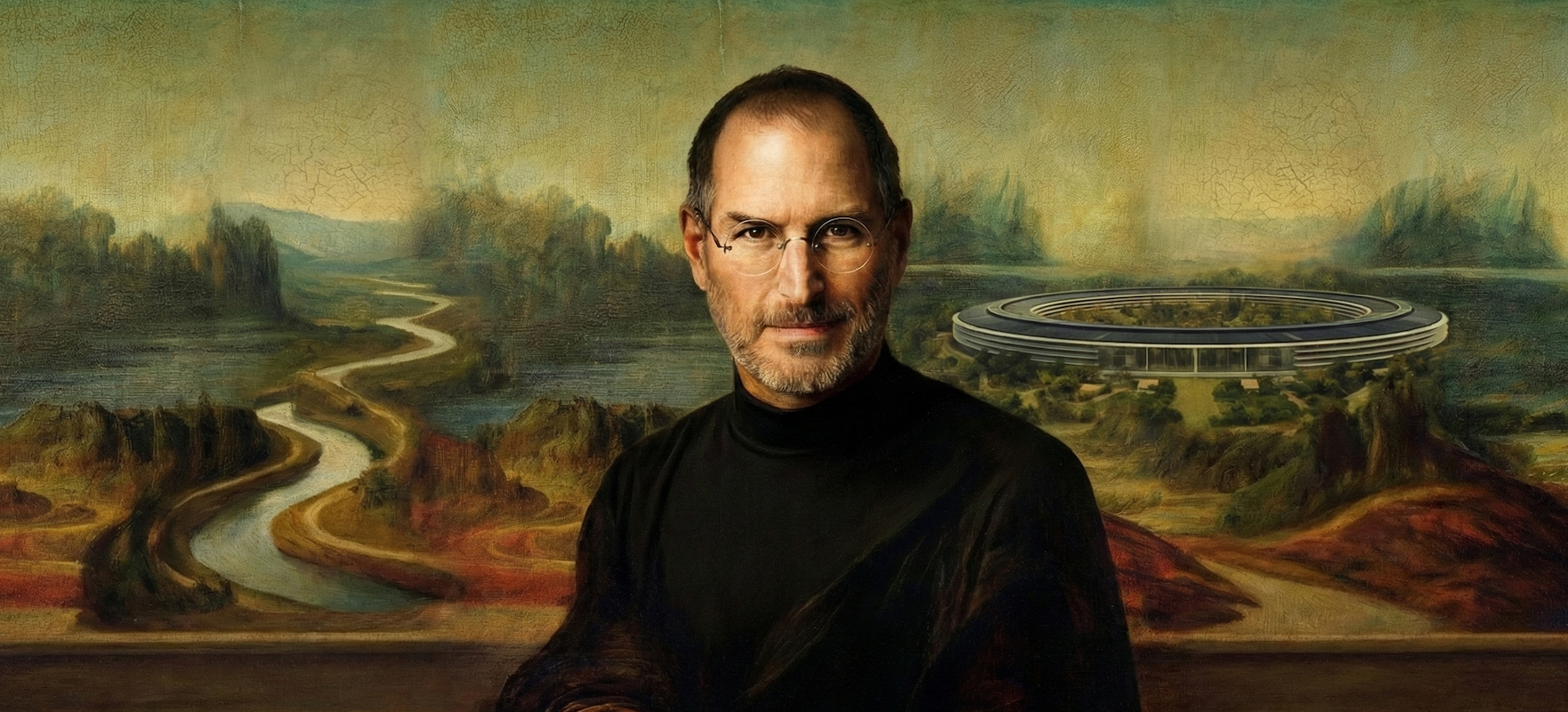

“Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication” was the headline of Apple’s first marketing brochure in 1977, borrowed from Leonardo da Vinci. Jobs spent the rest of his career demonstrating what that phrase actually meant.

“Simple can be harder than complex,” he explained. “You have to work hard to get your thinking clean to make it simple. But it’s worth it in the end because once you get there, you can move mountains.”

For the iPod interface, Jobs imposed a rigid test: if he wanted a song or function, he should be able to get there in three clicks, and each click should be intuitive. “There would be times when we’d wrack our brains on a user interface problem,” Tony Fadell recalled, “and think we’d considered every option, and he would go, ‘Did you think of this?’ He’d redefine the problem or approach, and our little problem would go away.”

When Apple’s best designers presented a streamlined iDVD design—the original required a thousand-page manual—Jobs walked to a whiteboard and drew a rectangle. “Here’s the new application,” he said. “It’s got one window. You drag your video into the window. Then you click the button that says ‘Burn.’ That’s it. That’s what we’re going to make.”

Apple University used Picasso’s 1945 lithograph series “The Bull” to teach this philosophy. The eleven prints show a bull progressively abstracted from detailed realism to essential lines. “You have to deeply understand the essence of a product,” Jobs taught, “in order to be able to get rid of the parts that are not essential.”

A business strategist hiding in an artist’s clothes

The popular image of Jobs emphasizes his aesthetic obsessions, but he was simultaneously a shrewd business strategist who built what may be the most successful consumer technology company in history. His business intelligence operated on multiple levels simultaneously.

Market timing was perhaps his greatest strength. The iPod launched in October 2001, after Jobs recognized that MP3 players lacked quality products despite a growing market. He waited for the technology to mature—specifically, the Toshiba hard drive that made “1,000 songs in your pocket” possible—then moved decisively. The iPhone launched in 2007 only after multi-touch displays, processing power, and cellular networks had all reached adequate maturity.

His competitive analysis was brutal and clear-eyed. “The problem with Microsoft is they have no taste,” he famously said. “I have no problem with Microsoft’s success. I have a problem with the fact that they just make really third-rate products.” On Dell, after the CEO suggested Apple should “shut it down and give the money back to shareholders,” Jobs displayed a bullseye over Dell’s picture at Macworld: “We’re coming after you, buddy.”

But Jobs was pragmatic when necessary. Upon returning to Apple in 1997, he shocked the audience by accepting a $150 million investment from Microsoft and announcing continued Office development for Mac. “We have to let go of the notion that for Apple to win, Microsoft has to lose.”

His pricing strategy never wavered from premium positioning. When John Sculley wanted to sell the original Macintosh for $1,999, Jobs pushed for $2,499 to protect Apple’s traditional 40% gross margin. Apple never competed on price. “We never had an objective to sell a low-cost phone,” Tim Cook later explained. “Our primary objective is to sell a great phone.”

The Tim Cook partnership, beginning in 1998, transformed Apple’s operations. In seven months, Cook slashed inventory from thirty days to six days, reduced suppliers from over one hundred to twenty-four, and cut warehouses by half. His famous view: “Inventory is fundamentally evil. Inventory is like dairy products.” Jobs embraced this operational excellence as essential to product quality. “Manufacturing demands just as much thought and strategy as the product,” he said. “Some companies view manufacturing as a necessary evil. We view it instead as a tremendous opportunity to gain competitive advantage.”

His boldest strategic move was self-cannibalization. On September 7, 2005, Jobs discontinued the wildly successful iPod Mini—Apple’s best-selling product—to launch the iPod Nano. The first million Nanos sold in seventeen days. “Competitors were beginning to catch up,” he explained. Better to eat your own lunch than let someone else eat it.

The keynote as theater

Jobs’ product presentations achieved a kind of legendary status—and for good reason. He prepared for major keynotes like an actor preparing for opening night, clearing his calendar a full month beforehand to rehearse.

He practiced the entire presentation aloud for many hours, going through it a dozen times minimum. Two full days before each keynote, he conducted complete dress rehearsals in the actual venue. Ken Kocienda, an Apple designer, explained: “This was one of Steve’s great secrets of success as a presenter. He practiced. A lot. He went over and over the material until he had the presentation honed and he knew it cold.”

The presentations followed a careful structure based on the Rule of Three, reflecting Jobs’ understanding that short-term memory retains limited information. At the iPhone launch in 2007, he announced: “Today we’re introducing three revolutionary products”—before revealing they were all one device.

His slides contained no bullet points, ever. Just images, photographs, or phrases of only a few words. Each slide conveyed a single idea, requiring Jobs to internalize the entire narrative rather than reading from prompts. The 80-minute iPhone introduction required no notes.

The “One More Thing” technique, borrowed from Peter Falk’s Detective Columbo, became Jobs’ signature. He would wrap things up, appear to leave, then turn back: “But there’s one more thing…” The technique debuted in 1999 with the AirPort Wi-Fi router. His most iconic usage came in 2008, when he pulled the impossibly thin MacBook Air from a manila envelope.

The 2007 iPhone demo was actually a miracle of performance under pressure. The device was an incomplete prototype that would crash if tasks were performed out of order. Engineers developed a “golden path”—specific features demonstrated in specific sequence to avoid disasters. The phone was programmed to always show five bars of signal strength regardless of actual signal. Engineers sat in the fifth row drinking Scotch, taking shots each time their feature worked.

The brutal honesty that built a culture

Jobs’ feedback came in three basic formats: “It’s great,” “It’s not bad, but change this, this, and that,” and—most commonly for first versions—”It sucks.” When asked in a 1995 interview what it meant when he told someone their work was “shit,” Jobs replied: “It usually means their work is shit. Sometimes it means, ‘I think your work is shit, and I’m wrong.’ But usually it means their work is not anywhere near good enough.”

At NeXT, employees dubbed his binary emotional swings the “hero/shithead roller-coaster.” You were either a genius or worthless, with no middle ground.

The MobileMe launch disaster of 2008 demonstrated his volcanic response to failure. After Walt Mossberg published a negative review, Jobs gathered the entire team of approximately one hundred people in Apple’s auditorium. “Can anyone tell me what MobileMe is supposed to do?” he asked. When an employee answered, Jobs snapped: “So why the fuck doesn’t it do that?” He spent an hour berating the group, then fired the team leader on the spot in front of everyone.

An engineering project manager present offered a devastating critique: the line-level engineers had warned leadership that the launch was too aggressive but were overruled. “He made himself so fearful and so terrible that an entire group of amazing, talented, hardworking people ended up getting screamed at wrongfully. It was his fault that the MobileMe launch went so poorly, not ours.”

Yet most colleagues theorized the harshness was designed to extract their best work. “I was incredibly grateful for the apparently harsh treatment Steve had dished out the first time,” recalled one employee. “He forced me to work harder, and in the end I did a much better job than I would have otherwise.”

Jobs was self-aware about his reputation. He once called Fortune’s editor to complain about an article, then paused: “Wait a minute, you’ve discovered that I’m an asshole? Why is that news?”

When the baton dropped

On May 31, 1985, Steve Jobs was stripped of all authority at Apple by the board of directors, siding with CEO John Sculley. Hours later, he sat “bewildered and puffy-eyed on a mattress in his nearly furniture-less 30-room mansion.”

“I feel like somebody just punched me in the stomach and knocked all my wind out,” he wrote in a farewell letter. “I’m only 30 years old and I want to have a chance to continue creating things. I know I’ve got at least one more great computer in me. And Apple is not going to give me a chance to do that.”

The firing haunted him for years. In 1996, eleven years later, he was still bitter: “What can I say? I hired the wrong guy. He destroyed everything I spent ten years working for.”

But Jobs eventually reframed the experience. At Stanford in 2005, he told graduates: “I didn’t see it then, but it turned out that getting fired from Apple was the best thing that could have ever happened to me. The heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again, less sure about everything. It freed me to enter one of the most creative periods of my life.”

The wilderness that forged a leader

Jobs founded NeXT Computer with money from his Apple stock sale and Ross Perot’s investment. The company was a commercial failure—selling only about 50,000 computers total over its lifetime. By 1993, Jobs was, as he later put it, “in ankle-deep shit.” He folded the hardware operation, laid off most of the staff, and stopped going to work for stretches, spending days at home with his young son.

Multiple observers who knew Jobs before and after the wilderness years testified to his transformation. Tim Bajarin of Creative Strategies concluded: “I am convinced that he would not have been as successful after his return at Apple if he hadn’t gone through his wilderness experience at NeXT.” Historian Randall Stross agreed: “The Steve Jobs who returned to Apple was a much more capable leader—precisely because he had been badly banged up.”

What did he learn? How to delegate, after initially designing everything from office furnishings to the finish on internal screws. How to listen to advice, after seven vice presidents left or were fired between 1992 and 1993. How to retain talent—Apple later had a remarkably stable executive team, a direct result of lessons learned the hard way.

The technology from NeXT ultimately became the foundation of macOS. Darwin, the core of Apple’s operating systems, derived directly from NeXTSTEP. When Apple acquired NeXT for $400 million in December 1996, it got not just Jobs but the software architecture that would power every Apple device for the next quarter century.

Pixar’s unexpected gift

Jobs purchased the Graphics Group from George Lucas in 1986 for $10 million. The company had negative $50 million net worth. Its initial business model—selling high-end Pixar Image Computers at $135,000 each—resulted in only about one hundred machines sold ever.

For nearly a decade, Jobs personally invested approximately $50 million to keep Pixar alive. Ed Catmull and Alvy Ray Smith approached thirty-five venture capitalists; all said no. Jobs considered selling to companies ranging from Hallmark to Microsoft. By the early 1990s, Pixar was “limping on, making animated shorts and special effects for TV commercials.”

Then came Toy Story. Released in November 1995, it opened to $30 million and eventually grossed $365 million globally. Days later, Pixar went public at $39 per share. The once-struggling company was valued at $1.5 billion.

What Pixar taught Jobs was perhaps more valuable than the eventual $7.4 billion Disney paid for it in 2006. He learned from Ed Catmull’s management philosophy—collaborative, diplomatic, protective of creative teams from corporate pressure. Crucially, Jobs did not insert himself into Pixar’s creative process. This self-restraint, “a testament to his respect for Lasseter and the other artists,” represented growth. He learned that trusting creative teams produced better outcomes than micromanagement.

As one assessment put it: “The failures, stinging reversals, miscommunications, bad judgment calls, emphases on wrong values—the whole Pandora’s box of immaturity—were necessary prerequisites to the clarity, moderation, reflection, and steadiness he would display in later years.”

Ninety days from insolvency

When Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, the company had lost over $1 billion in a year, laid off 3,800 employees, and watched its market share slide from 20% to 8%. It was ninety days from insolvency. Michael Dell famously suggested Apple should “shut it down and give the money back to the shareholders.”

Jobs moved with decisive clarity. He drew a simple 2×2 grid on a whiteboard: Consumer Desktop, Consumer Portable, Professional Desktop, Professional Portable. Everything else—the Newton PDA, countless product variants, research projects—was eliminated. He cut 70% of Apple’s product line. “We were selling a lot of crap,” he explained.

The “Think Different” campaign reclaimed Apple’s spiritual identity, aligning the company with “the misfits, the rebels, the troublemakers, the round pegs in the square holes.” Jobs later recalled: “I came out of the meeting with people who had just gotten their project canceled, and they were three feet off the ground with excitement because they finally understood where the heck we were going.”

Within a year, Apple went from losing $1.04 billion to making $309 million in profit. The iMac launched in 1998—translucent, friendly, all-in-one. Then the iPod in 2001, the iPhone in 2007, the iPad in 2010. Each product built on the last, creating an ecosystem that locked in customers while delighting them.

The mirror every morning

Jobs was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in October 2003— specifically, a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor, a rare and slower-growing form. Against his doctors’ recommendations, he pursued alternative treatments for nine months: vegan diets, acupuncture, herbal remedies, juice fasts. “I really didn’t want them to open up my body,” he later explained. He eventually expressed regret about the delay.

In July 2004, he finally underwent surgery. Surgeons discovered three liver metastases. In March 2009, he received a liver transplant in Memphis after a young man in his mid-twenties died in a car crash. Tim Cook had offered a portion of his own liver; Jobs refused. He developed pneumonia after the transplant; his children were summoned to say their goodbyes. He pulled through.

The proximity of death clarified everything. “For the past 33 years, I have looked in the mirror every morning and asked myself: ‘If today were the last day of my life, would I want to do what I am about to do today?’” he told Stanford graduates. “And whenever the answer has been ‘No’ for too many days in a row, I know I need to change something.”

His meditation on mortality became the speech’s most quoted passage: “Remembering that I’ll be dead soon is the most important tool I’ve ever encountered to help me make the big choices in life. Because almost everything—all external expectations, all pride, all fear of embarrassment or failure—these things just fall away in the face of death, leaving only what is truly important.”

He offered graduates a provocative reframe: “Death is very likely the single best invention of life. It’s life’s change agent. It clears out the old to make way for the new.”

What the seeker finally understood

Everyone who attended Steve Jobs’ memorial service received a small brown box. Inside was a copy of Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramahansa Yogananda—a book Jobs had first read in India in 1974 and returned to throughout his life. The gift was his final message: that despite building the world’s most valuable technology company, he never stopped being the barefoot seeker who traveled to the Himalayas looking for something he couldn’t name.

The contradiction defined him. He was brutally pragmatic about business and mystically convinced that intuition revealed truths data could never capture. He was impatient beyond reason with imperfection yet capable of patient iteration over years. He damaged people with his cruelty and inspired them to achievements they couldn’t have imagined.

Perhaps the most revealing detail comes from Jony Ive’s eulogy: “He cared the most. He worried the most deeply. He constantly questioned: is this good enough? Is this right?” The harshness, the reality distortion, the obsessive control—all emerged from a fundamental anxiety that the work might not be worthy, that the opportunity to create something meaningful might be squandered.

Jobs’ life suggests that vision alone accomplishes nothing. It requires the complementary capacities he spent his wilderness years developing: the ability to trust others, to build organizations that can execute, to know when to fight and when to compromise. The young Jobs who couldn’t sit still for meditation became the older Jobs who could focus an entire company on four products in a two-by-two grid.

His final words, according to his sister Mona Simpson, were “Oh wow. Oh wow. Oh wow.” We don’t know what he saw. But we know what he left behind: proof that one person, thinking differently, can bend the future toward their vision—and that the bending requires everything, including the willingness to be broken first.

Stay hungry. Stay foolish.

- 35+ Steve Jobs Quotes That Will Revolutionize Your Thinking – https://thestrive.co/steve-jobs-quotes-on-success/

- What can we learn from Steve Jobs about complementary and alternative therapies? – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4924574/

- He quit his College, Came India on a Spiritual Journey – https://www.starsai.com/steve-jobs-spiritual-india/

- How Steve Jobs found Buddhism – https://www.lionsroar.com/how-steve-jobs-found-buddhism/

- Steve Jobs’ trip to India – https://medium.com/macoclock/how-much-did-coming-to-india-contribute-to-steve-jobs-endeavour-to-shape-apple-into-what-it-is-6c01b6054113

- How Zen Buddhism Inspired Steve Jobs to ‘Think Different’ – https://www.thevintagenews.com/2018/10/03/steve-jobs/

- About Kōbun, Steve Jobs Zen teacher – https://www.zenprogrammer.org/en/blog/steve-jobs-zen-teacher.html

- How Steve Jobs Trained His Own Brain – https://www.inc.com/geoffrey-james/how-steve-jobs-trained-his-own-brain.html

- Steve Jobs and the Rediscovery of Zen – https://www.nippon.com/en/views/b06101/

- Steve Jobs Had LSD. We Have the iPhone – https://healthland.time.com/2011/10/06/jobs-had-lsd-we-have-the-iphone/

- Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson: A Biography – https://agentpalmer.com/13459/media/the-written-word/steve-jobs-by-walter-isaacson-a-biography-of-the-man-from-the-intersection-of-humanities-and-sciences/

- ‘You’ve got to find what you love,’ Jobs says (Stanford) – https://news.stanford.edu/stories/2005/06/youve-got-find-love-jobs-says

- Steve Jobs and Reed College – https://www.reed.edu/about/steve-jobs.html

- One More Thing (McGraw-Hill) – https://www.accessengineeringlibrary.com/content/book/9780071636087/back-matter/appendix6

- How Steve Jobs’ Love of Simplicity Fueled A Design Revolution – https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/how-steve-jobs-love-of-simplicity-fueled-a-design-revolution-23868877/

- Steve Jobs’ 2005 Stanford Commencement Address – https://quartr.com/insights/business-philosophy/steve-jobs-2005-stanford-commencement-speech

- Steve Jobs Stanford Commencement Address (2005) – https://fs.blog/steve-jobs-stanford-commencement/

- Steve Jobs, Calligraphy, Lloyd Reynolds and Reed College – https://www.girvin.com/steve-jobs-calligraphy-lloyd-reynolds-and-reed-college/

- Steve Jobs’ Famous Speech – New Normal – https://fromtheexpertsmouth.com/steve-jobs-famous-speech-new-normal/

- Why Steve Jobs’s Passion for Calligraphy Is an Important Example – https://www.entrepreneur.com/leadership/why-steve-jobss-passion-for-calligraphy-is-an-important/377943

- Steve Jobs on Creativity – https://fs.blog/steve-jobs-on-creativity/

- How did Steve Jobs use the blend of technology and liberal arts – https://youexec.com/questions/how-did-steve-jobs-use-the-blend-of-technology-and-libe

- The most ignored advice from Steve Jobs – https://medium.com/swlh/the-most-ignored-advice-from-steve-jobs-and-how-it-can-be-your-secret-weapon-3995c51d54fc

- Working with Steve Jobs – https://www.deciphr.ai/podcast/281-working-with-steve-jobs

- The Real Leadership Lessons of Steve Jobs (HBR) – https://sites.nicholas.duke.edu/delmeminfo/files/2012/07/The-Real-Leadership-Lessons-of-Steve-Jobs-HBR-l-Apr-2012.pdf

- How Steve Jobs’ odd habit can help you brainstorm ideas – https://www.cnbc.com/2018/05/08/how-steve-jobs-odd-habit-can-help-you-brainstorm-ideas.html

- Zen Buddhism and Steve Jobs – http://issuesinperspective.com/2011/11/11-11-26-2/

- Focus means saying ‘no’, by Steve Jobs – https://rowansimpson.com/quotes/focus/

- Steve Jobs Quotes (Goodreads) – https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/5255891.Steve_Jobs

- Innovation is saying ‘no’ to 1000 things – https://quotefancy.com/quote/911687/Steve-Jobs-Innovation-is-saying-no-to-1-000-things

- 15 of the Top Steve Jobs Quotes About Innovation – https://www.indigo9digital.com/blog//9-of-the-best-steve-jobs-quotes-about-innovation-that-you-should-read-today

- Steve Jobs: Innovation is Saying “No” to 1,000 things – https://zurb.com/blog/steve-jobs-innovation-is-saying-no-to-1-0

- Steve Jobs’ 7 Rules: A Blueprint for IT Career Success – https://www.conceptualtech.com/blog/articles/2024-06-05_12_53_steve-jobs-7-rules-blueprint-career-success-michael-ferrara-kq73e.html

- Reality distortion field (Wikipedia) – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reality_distortion_field

- How Steve Jobs Created the Reality Distortion Field – https://jhargrave.medium.com/how-steve-jobs-created-the-reality-distortion-field-and-you-can-too-4ba87781adba

- Folklore.org: Reality Distortion Field – https://www.folklore.org/Reality_Distortion_Field.html

- Enough with the Reality Distortion Field – https://blog.chemistrystaffing.com/enough-with-the-reality-distortion-field

- Steve Jobs’ Reality Distortion Field – https://www.playforthoughts.com/blog/steve-jobs-reality-distortion-field

- Corning CEO says Steve Jobs pressured him – https://fortune.com/2025/10/23/steve-jobs-pressured-corning-wendell-weeks-first-apple-iphone-screens-youre-afraid/

- On Influence – https://www.codemag.com/article/1112011/On-Influence

- Steve Jobs believed saving seconds on start-up time would have a major impact – https://www.gamepressure.com/newsroom/its-a-matter-of-life-and-death-steve-jobs-believed-saving-seconds/z080a7

- How Steve Jobs’ iPod developed – https://xreart.com/blogs/blog/how-steve-jobs-ipod-developed

- Steve Jobs and Apple: A life (CBS News) – https://www.cbsnews.com/media/steve-jobs-and-apple-a-life-57526300/

- Zen and the Design Thinking Mindset of Steve Jobs – https://globisinsights.com/globis/yoshito-hori/steve-jobs-design-thinking-mindset/

- Steve Jobs Quotes About Simplicity – https://www.azquotes.com/author/7449-Steve_Jobs/tag/simplicity

- Understanding Steve Jobs’ Design Philosophy – https://press.farm/understanding-steve-jobs-design-philosophy/

- How did a work by Pablo Picasso inspire Steve Jobs – https://artshortlist.com/en/journal/article/apple-design-pablo-picasso-steve-jobs

- Simplicity as Innovation: What Picasso and Steve Jobs Can Teach You – https://medium.com/@briansolis/simplicity-as-innovation-what-picasso-and-steve-jobs-can-teach-you-about-game-changing-design-114c14dc303e

- Steve Jobs Quotes (IDRlabs) – https://www.idrlabs.com/quotes/steve-jobs.php

- When Jobs Painted a Bullseye on Michael Dell – https://techpp.com/2019/03/18/steve-jobs-michael-dell-believe-tech-or-not/

- Steve’s Job: Restart Apple (Time 1997) – https://allaboutstevejobs.com/verbatim/interviews/time_1997

- Brand Pricing Strategy: The Early Apple Way – https://brandingstrategyinsider.com/brand-pricing-strategy-the-early-apple-way/

- Understanding Apple’s Pricing Strategies – https://www.siliconindia.com/news/general/understanding-apples-pricing-strategies-lessons-to-learn-nid-214478-cid-1.html

- Tim Cook and Steve Jobs: A Legendary Partnership – https://www.ceotodaymagazine.com/2025/02/tim-cook-and-steve-jobs-a-legendary-partnership-that-shaped-apple/

- Tim Cook and the Power of Supply Chain Innovation – https://mediasupplychain.org/tim-cook-and-the-power-of-supply-chain-innovation/

- Tim Cook: Supply chain guru behind Apple growth – https://supplychaindigital.com/technology/tim-cook-supply-chain-guru-behind-apple-growth

- Quotes (all about Steve Jobs) – https://allaboutstevejobs.com/verbatim/quotes

- Follow Steve Jobs’s 5-Step Presentation Process – https://www.inc.com/carmine-gallo/follow-steve-jobs-5-step-presentation-process-to-wow-your-audience.html

- Steve Jobs’s Presentation Techniques Revealed – https://www.bestpresentation.net/presentation-secrets-steve-jobs/

- Deliver a Presentation like Steve Jobs – https://www.k4northwest.com/articles/deliver-a-presentation-like-steve-jobs

- Steve Jobs Practiced 1 Habit That Turned Good Presentations Into Great Ones – https://www.inc.com/carmine-gallo/steve-jobs-practiced-1-habit-that-turned-good-presentations-into-great-ones.html

- Steve Jobs’s 6-Step Rehearsal Process – https://www.inc.com/carmine-gallo/a-long-time-apple-designer-reveals-steve-jobs-6-step-rehearsal-process-he-used-for-every-presentation.html

- How to Present Like Steve Jobs – https://davelinehan.com/how-to-present-like-steve-jobs/

- 16 Years ago today, Steve Jobs introduced the iPhone – https://www.patentlyapple.com/2023/01/in-2007-16-years-ago-today-steve-jobs-introduced-the-revolutionary-iphone.html

- One more thing in Apple’s history – https://medium.com/@subah.popli.24n/one-more-thing-in-apple-s-history-fd9ffeaaacdc

- Behind-the-scenes details revealed about Steve Jobs’ first iPhone announcement – https://appleinsider.com/articles/13/10/04/behind-the-scenes-details-reveal-steve-jobs-first-iphone-announcement

- Former Apple Engineer Gives Behind-the-Scenes Look at the Original iPhone Introduction – https://www.macrumors.com/2013/10/04/former-apple-engineer-gives-behind-the-scenes-look-at-the-original-iphone-introduction/

- Steve at Work – https://allaboutstevejobs.com/persona/steve_at_work

- “Your Work Is Shit”: Steve Jobs on Negative Feedback – https://garyborjesson.wordpress.com/2013/07/20/your-work-is-shit-steve-jobs-on-negative-feedback/

- How Founders Must Channel Shame – https://medium.com/initialized-capital/how-founders-must-channel-shame-51baab69ca45

- Steve Jobs: The Wilderness, 1985-1997 (Bloomberg) – https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2011-10-06/steve-jobs-the-wilderness-1985-1997

- Showdown at Apple: John Sculley vs. Steve Jobs – https://www.mac-history.net/showdown-at-apple-john-sculley-vs-steve-jobs/

- Steve Jobs (Wikiquote) – https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Steve_Jobs

- 8 Unforgivable Leadership Mistakes Steve Jobs Made – https://www.sandersconsulting.com/8-unforgivable-leadership-mistakes-steve-jobs-made/

- Lessons from Steve Jobs: How to Recover from Failure – https://www.edutopia.org/blog/steve-jobs-failure-recovery-eric-brunsell

- What Is Steve Jobs’ NeXT? Inside the ‘Failure’ That Reinvented Apple – https://applescoop.org/story/what-is-steve-jobs-next-inside-the-failure-that-reinvented-apple

- Steve Jobs (Wikipedia) – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steve_Jobs

- Steve Jobs (Apple Wiki Fandom) – https://apple.fandom.com/wiki/Steve_Jobs

- The Wilderness Years (Newsweek) – https://www.newsweek.com/wilderness-years-68157

- What Steve Jobs (and I) learned in the wilderness – https://headhearthand.org/blog/2010/11/23/what-steve-jobs-and-i-learned-in-the-wilderness/

- Darwin (operating system) – https://en-academic.com/dic.nsf/enwiki/33851

- Steve Jobs’ Involvement in Pixar – https://press.farm/steve-jobs-involvement-in-pixar-and-animation/

- Steve Jobs The Pixar Story – https://www.deciphr.ai/podcast/235-steve-jobs-the-pixar-story

- How Steve Jobs Changed the Course of Animation – https://www.biography.com/business-leaders/steve-jobs-pixar-animation-history

- The Steve Jobs Pixar Story: How He Almost Went Bankrupt – https://slidebean.com/story/steve-jobs-pixar-animation-history

- Steve Jobs (Isaacson biography excerpt) – http://edu.szmdata.com/Novels/Steve%20Jobs/xhtml/ch22.html

- Becoming Steve Jobs: The Evolution of a Reckless Upstart – https://world.hey.com/davidsenra/becoming-steve-jobs-the-evolution-of-a-reckless-upstart-into-a-visionary-leader-21fe8fa8

- Lessons from the Successes of Steve Jobs: Focus, Focus Focus – https://onstrategyhq.com/resources/lessons-from-the-successes-of-steve-jobs-focus-focus-focus/

- Steve Jobs Apple Comeback Strategy – https://yourstory.com/2024/09/steve-jobs-apple-comeback-strategy-tech-giant-success

- How Steve Jobs Saved Apple – https://www.entrepreneur.com/growing-a-business/how-steve-jobs-saved-apple/220604

- Here’s how Steve Jobs smacked down Michael Dell on stage – https://www.alphr.com/apple/1001703/heres-how-steve-jobs-smacked-down-michael-dell-on-stage/

- 25 Years Ago, Steve Jobs Saved Apple From Collapse – https://www.inc.com/nick-hobson/25-years-ago-steve-jobs-saved-apple-from-collapse-its-a-lesson-for-every-tech-ceo-today.html

- iPhone outgrew Steve Jobs’ product strategy – https://9to5mac.com/2025/11/14/iphone-outgrew-steve-jobs-product-strategy-and-more-change-is-coming/

- How Steve Jobs’ Trip to India Shaped Apple Design Philosophy – https://medium.com/@abhayaditya/how-steve-jobs-trip-to-india-shaped-apple-design-philosophy-7cae4b66e99c

- How Steve Jobs’ “Think Different” Speech Saved Apple – https://blog-origin.mediashower.com/blog/steve-jobs-1997-speech/

- Steve Jobs (Britannica Money) – https://www.britannica.com/money/Steve-Jobs/Saving-Apple

- Famous People Who Have Passed from NETs: Steve Jobs – https://neuroendocrine.org.au/news/famous-people-who-have-passed-from-nets-steve-jobs/

- Steve Jobs chose herbal medicine, delayed cancer surgery – https://www.cbc.ca/news/science/steve-jobs-chose-herbal-medicine-delayed-cancer-surgery-1.1124855

- Records Reveal Preventable Deaths at Memphis Transplant Center – https://www.propublica.org/article/james-eason-methodist-memphis-liver-transplant

- Memphis doctor recalls time spent saving Steve Jobs’ life – https://www.actionnews5.com/story/16102042/memphis-doctor-recalls-time-spent-saving-steve-jobs-life/

- Steve Jobs Stanford University Inspirational Speech – https://www.motivateamazebegreat.com/2014/05/steve-jobs-stanford-university.html

- Steve Jobs Speech (ResearchGate) – https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301899412_Steve_Jobs_Speech

- 7 Lessons from Steve Jobs’ Commencement Speech – https://www.sahilbloom.com/newsletter/7-lessons-from-steve-jobs-commencement-speech

Leave a Reply